BradenLive

Things I write live here

What is AI and how do we measure it?

This summer, I interned at an AI startup called Narrative Science, working on a product called Lexio as a product manager. Lexio connects to a customer’s Salesforce data and uses natural language generation (NLG) to write stories about the data - for example, replacing the status update a sales rep might send their boss at the end of every week. I knew the product was AI because it replaced work that a human was doing.

In the fall, while taking classes at Kellogg, I interned at Tensility Venture Partners, a seed-stage VC firm focused on enterprise applications of AI. I had the opportunity to sit through more than 50 founders pitching their AI startups. We viewed products as truly AI if the product was not only predictive, but prescriptive - giving actionable information to achieve a specific outcome.

Throughout these internships and in my classes at Kellogg, I’ve never found a good definition of AI. Machine learning models can be prescriptive; for example, next product to buy algorithms can tell a marketer when and which marketing email to send to customers in order to maximize purchases. But machine learning is just statistics - it’s not intelligent as humans would recognize it. From XKCD:

The Oxford Dictionary defines AI as

the theory and development of computer systems able to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence, such as visual perception, speech recognition, decision-making, and translation between languages.

but this leaves me wanting more as well. Recent heralded advances in supposed AI like AlphaGo and OpenAI Five play games that humans normally play, beating the best humans in the world. But can these intelligent machines drive a car? or even navigate a maze?

The Measure of Intelligence

Reading Francois Chollet’s latest paper, The Measure of Intelligence gave me a much better understanding of how to evaluate AI. Chollet proposes an actionable definition for AI as well as a way to measure it. His goal is

to point out the implicit assumptions our field has been working from, correct some of its most salient biases, and provide an actionable formal definition and measurement benchmark for human-like general intelligence, leveraging modern insight from developmental cognitive psychology.

The paper is organized into three sections: first, Chollet provides context and history around intelligence and AI, how both have been classically defined, and how this has impacted research into AI. Second, he proposes a new definition for AI. Finally, he provides a new dataset that can be used to benchmark AI against a formal definition of AI. I found all three sections to be extraordinarily useful in understanding AI and how to best think about it. What follows is my main takeaways from the paper.

Context and history

Traditionally, the fields of cognitive science and psychology has struggled to define intelligence. There have been two diverging visions for defining intelligence:

- The mind is a “relatively static assembly of special purpose mechanisms developed by evolution, only capable of learning what it is programmed to acquire”

- The mind is a “general purpose ‘blank slate’ capable of turning arbitrary experience into knowledge and skills, and that could be directed at any problem.”

In terms of human evolution, I tend to lean towards the latter view. How could a mind evolve into a collection of special purpose mechanisms? How did it know ahead of time what mechanisms to prioritize unless it first started as a blank slate?

At a very high level, it appears that much of the so-called progress in AI recently has been in favor of the former. AI algorithms are specially built to accomplish very specific tasks, but struggle when presented with a new task even if that new task is very similar–for example, some computer vision applications have trouble recognizing images that have been turned sideways. Other well-known examples of AI that out-perform humans in certain tasks but exhibit no recognizable intelligence include applications in games like Chess (Deep Blue), Go (AlphaGo), or DotA2 (OpenAI Five).

Conversely, the rise of machine learning models, where AI “learns” its skills via the training data, can be viewed through the blank-slate lens.

Regardless, this dichotomy brings into focus some of the central issues at play in defining AI, and in pushing forward AI research. The interplay between “crystallized skills” (i.e., mechanisms developed by evolution in humans or in some manner hard-coded into AI algorithms) and ability to learn new skills are key in understanding and defining AI, and has been the fundamental difficulty in AI since its inception.

Finally, these competing visions also present difficulties when it comes to evaluating intelligence. We can either:

- measure skills (the static assembly of special-purpose mechanisms vision)

- measure broad abilities (the blank-slate vision)

Chollet describes the various methods that are currently used to evaluate AI, which include human review, white-box analysis, peer confrontation, and benchmarks. Flaws exist in each method; furthermore, models are not comparable to each other without an accepted overarching definition of intelligence.

A new definition for AI

The difficulties of defining intelligence, and thus proving progress towards it, are perfectly captured by Scott Alexander at Slate Star Codex. Two children debate the intelligence of an AI algorithm…then two chemists debate the intelligence of the children, then two angels debate the intelligence of the human chemists. Finally, God chimes in regarding the author of the story:

God sits in the highest heaven, alone.

“Wow!” He thinks to Himself, “that cellular automaton sure is producing some pretty patterns today. I wonder what it will do next!”

A century ago, the applications we use every day would likely have been regarded as intelligent–see Wolfram Alpha as a likely example of the wondrous nature of tools available to us today. However, today this is not regarded as intelligent. How can we set a definition for AI that won’t change as advancements are made, and is relevant to human intelligence?

Chollet proposes the following definition:

The intelligence of a system is a measure of its skill-acquisition efficiency over a scope of tasks, with respect to priors, experience, and generalization difficulty.

Importantly, “skill is merely the output of the process of intelligence.”

This is based on several intuitions described in the paper:

- “Intelligence lies in broad or general-purpose abilities; it is marked by adaptability and flexibility…rather than skill itself.” Skill can be a function of the amount of training data available, for example, and thus is not attributable to the level of intelligence itself

- “A measure of intelligence should control for experience and priors”

- “Intelligence and its measure are inherently tied to a scope of application. As such, general AI should be benchmarked against human intelligence and should be founded on a similar set of knowledge priors.”

Assuming this definition and accepting these intuitions as valid, then, means that general-purpose AI must “optimize directly for flexibility and generality rather than performance on any specific task.” I note that this approach seems to match how humans learn; in my own experience, I can optimize for performance on a purported test of intelligence (for example, the GMAT), yet in my opinion this approach does not actually measure my ability to understand and apply overarching concepts.

Conversely, in my experience as an EOD officer in the Navy, we learn general concepts for staying safe while handling explosives without memorizing specific protocols to enact in every situation. This leads to a much deeper understanding and hence performance. A technician who memorizes the manual and relies heavily on it will perform sub-optimally in new situations compared to a technician who understands how the concepts apply in that new situation.

A new dataset to evaluate AI

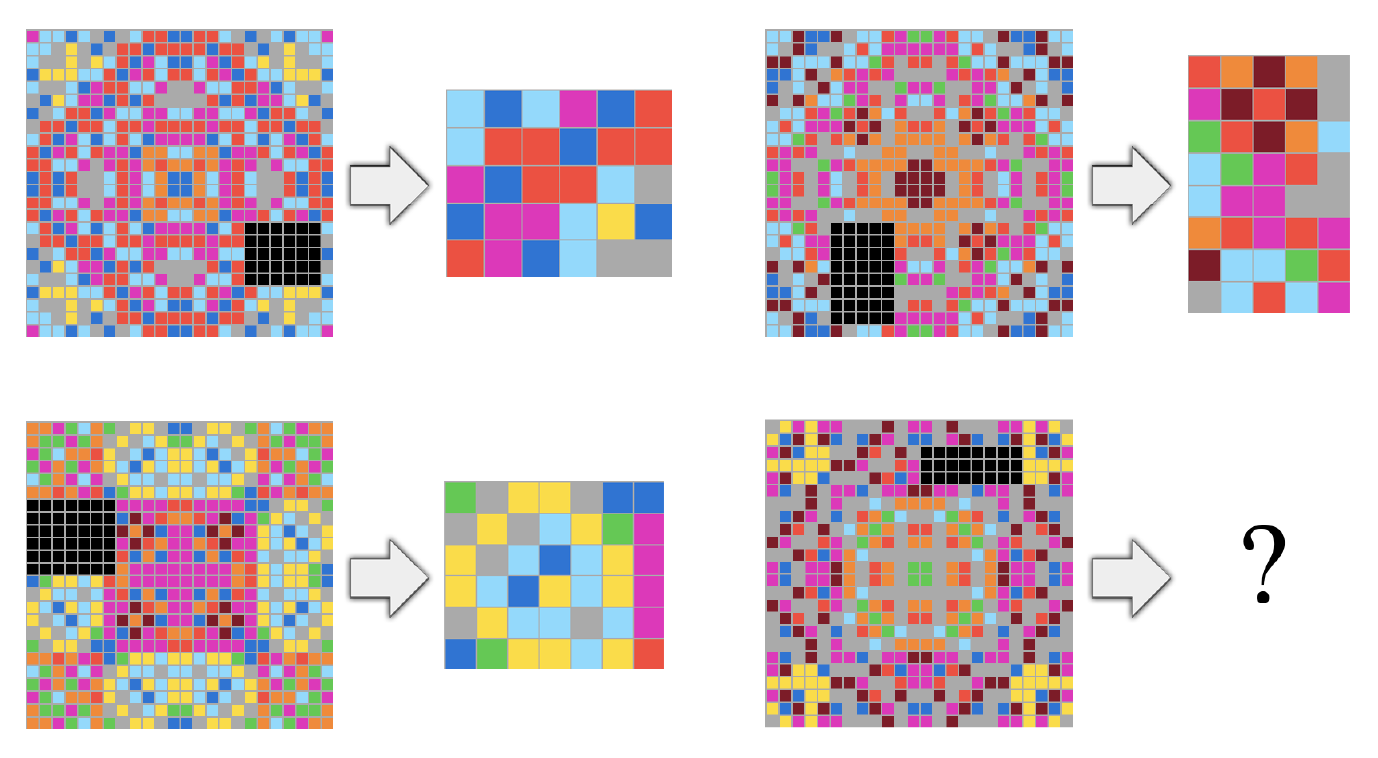

The Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus (ARC) is a new set of tasks that can be used to evaluate an AI. It is “targeted at both humans and artificially intelligent systems that aim at emulating a human-like form of general fluid intelligence.”

The dataset contains a total of 800 tasks (400 for training and 400 for testing), as well as an additional 200 tasks held back by Chollet for private evaluation. These tasks all resemble the above: several examples of each task are provided, and then the algorithm must complete the task based on the examples. All tasks are based on these grid images. The tasks were individually constructed by humans, rather than programmatically generated–this decreases the possibility that an AI could deduce the algorithm used to create the tasks and thereby work backwards to solve the tasks.

The tasks all rely on a specified list of priors (i.e., knowledge supplied by the AI creators) which are based on human cognitive priors. These priors include:

- Objectness

- object cohesion

- object persistence

- object influence via contact

- Goal-directedness

- Numbers and counting

- Basic geometry and topology

- frequency of simple shapes over complex ones

- symmetries

- shape upscaling/downscaling, elastic distortions

- containment, inside/outside a perimeter

- drawing lines, connecting points

- copying, repeating objects

The ARC is proposed as a better alternative to existing psychometric (IQ) tests:

Unlike some psychometric intelligence tests, ARC is not interested in assessing crystallized intelligence or crystallized cognitive abilities. ARC only assesses a general form of fluid intelligence, with a focus on reasoning and abstraction. ARC does not involve language, pictures of real-world objects, or real-world common sense. ARC seeks to only involve knowledge that stays close to Core Knowledge priors, and avoids knowledge that would have to be acquired by humans via task-specific practice.

The ARC is a simple, human-completable test that can be used to compare the general intelligence of AI systems to each other as well as to humans. Human performance on existing psychometric tests is predictive of success across all human cognitive tasks, so ARC can potentially also predict how practically valuable an AI will be relative to a human.

Final thoughts

I found this paper extremely readable. The insights into the history of AI and AI research, arguments for evaluating skill-acquisition rather than merely skill performance, and proposition of a concrete way to measure AI performance were all uniquely insightful. As AI continues to expand into every business vertical and impact our daily lives, I recommend that even non-technical leaders read the paper for free here: https://arxiv.org/abs/1911.01547.

My understanding of artificial intelligence and our long journey towards machines with human-comparable intelligence has been greatly increased. As we get closer to the day when those machines are an everyday reality, I am fascinated by a quote from over 350 years ago, and hope we can remain clear-headed about what AI is and what it is not:

Even though such machines might do some things as well as we do them, or perhaps even better, they would inevitably fail in others, which would reveal they were acting not through understanding, but only from the disposition of their organs. —Rene Descartes, 1637