BradenLive

Things I write live here

Accurately predicting an unlikely event

I follow several tech leaders on Twitter who were early voices sounding the alarm on COVID-19 - primarily Balaji Srinivasan and Scott Gottlieb. Normally, I’m fairly conservative and skeptical of warnings like these. Fortunately, however, Balaji, Scott, and others convinced me through their in-depth and informative tweets that COVID-19 was going to be a serious crisis in just a matter of a few weeks.

Fearing the impact of Coronavirus over a month ago, I took my family to Costco to stock up on food and home supplies on February 28th.

I didn’t start talking to my elderly parents, extended family or friends about my worries about Coronavirus (COVID-19) until March 11th.

On the face of it, this doesn’t add up. Why would I stock up on supplies to prepare for a possible lockdown or a run on the grocery stores (or worse) but not warn those most vulnerable at the same time? Did I act selfishly?

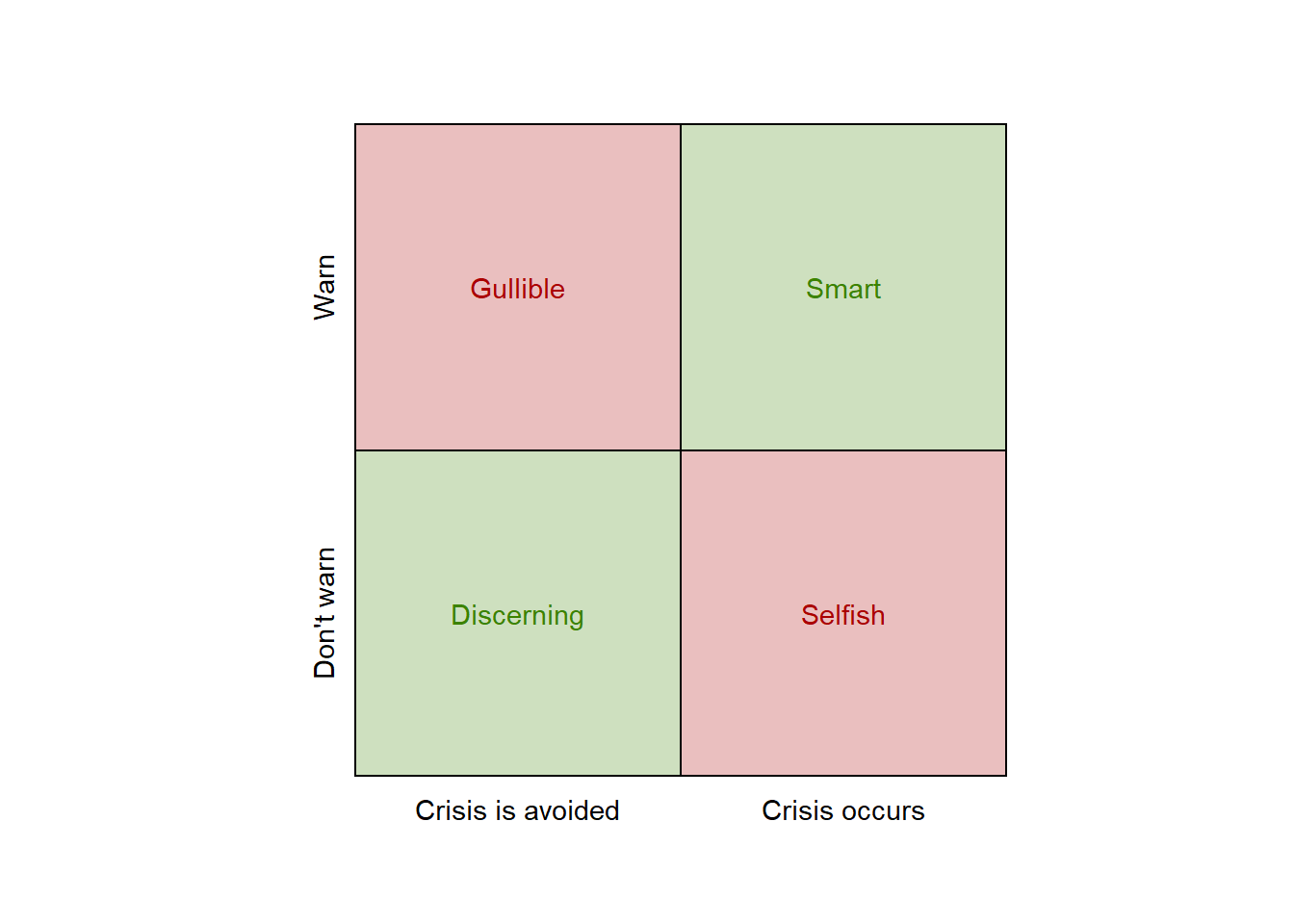

I struggled through the last few weeks wrestling with the optimal time to begin warning everyone. I saw four possible outcomes based on when/if I chose to warn those around me, and whether COVID-19 really did turn into a crisis worth warning anyone about:

I didn’t want to appear gullible by warning people – overreacting – about a non-existent threat, or selfish by not warning people about a crisis that I could have helped them avoid. I was weighing the well-being of those around me against my own ego - wanting to come out of this looking as good as possible and ensuring people would take me seriously in the future.

As Ian Bogost wrote in The Atlantic last week:

Risking overreaction means knowing, in advance, that a particular action might be extreme and carrying it out anyway. And doing so not under a cloud of nail-biting fear that you might look a fool if it turns out wrong, but in the hopes that having done so will make it turn out right. If it does, you who overreact will earn a response even worse than the shame of looking the fool: Like the heroes of Y2K, you will enjoy no response whatsoever.

“Growthers” and “Base-raters”

Tyler Cowen wrote for Bloomberg about two camps he termed growthers and base-raters. Growthers believe in the power of exponential growth, and have therefore been more bearish on the approaching impacts of COVID-19. Growthers appear to be concentrated in tech and finance, industries for which exponential growth is an everyday occurence: “the growthers find it easy to imagine that the number of cases might overwhelm the capacity of the U.S. health care system.”

Base-raters, on the other hand, give precedence to the idea that the impacts of COVID-19 are likely to be less severe, since severe incidents like world-wide pandemics occur so rarely: “The base-raters, when assessing the likelihood of a particular scenario, start by asking how often it has happened before.” Elected officials (at least until very recently) and much of middle America appears to fall into the base-raters camp.

Many of those who were skeptical of COVID-19 and telling people to worry about the flu now are partially responsible for the vast scale of the crisis in which we find ourselves. Cowen writes:

As for the health-care establishment, epidemiologists understand exponential growth rates very well. But many medical professionals think in terms of what are called “normal” statistical distributions. If someone visits your office with what appears to be a typical flu case, it is usually exactly that. The result is that there is not much surge capacity in America’s hospitals and public-health institutions.

How do we avoid this in the future?

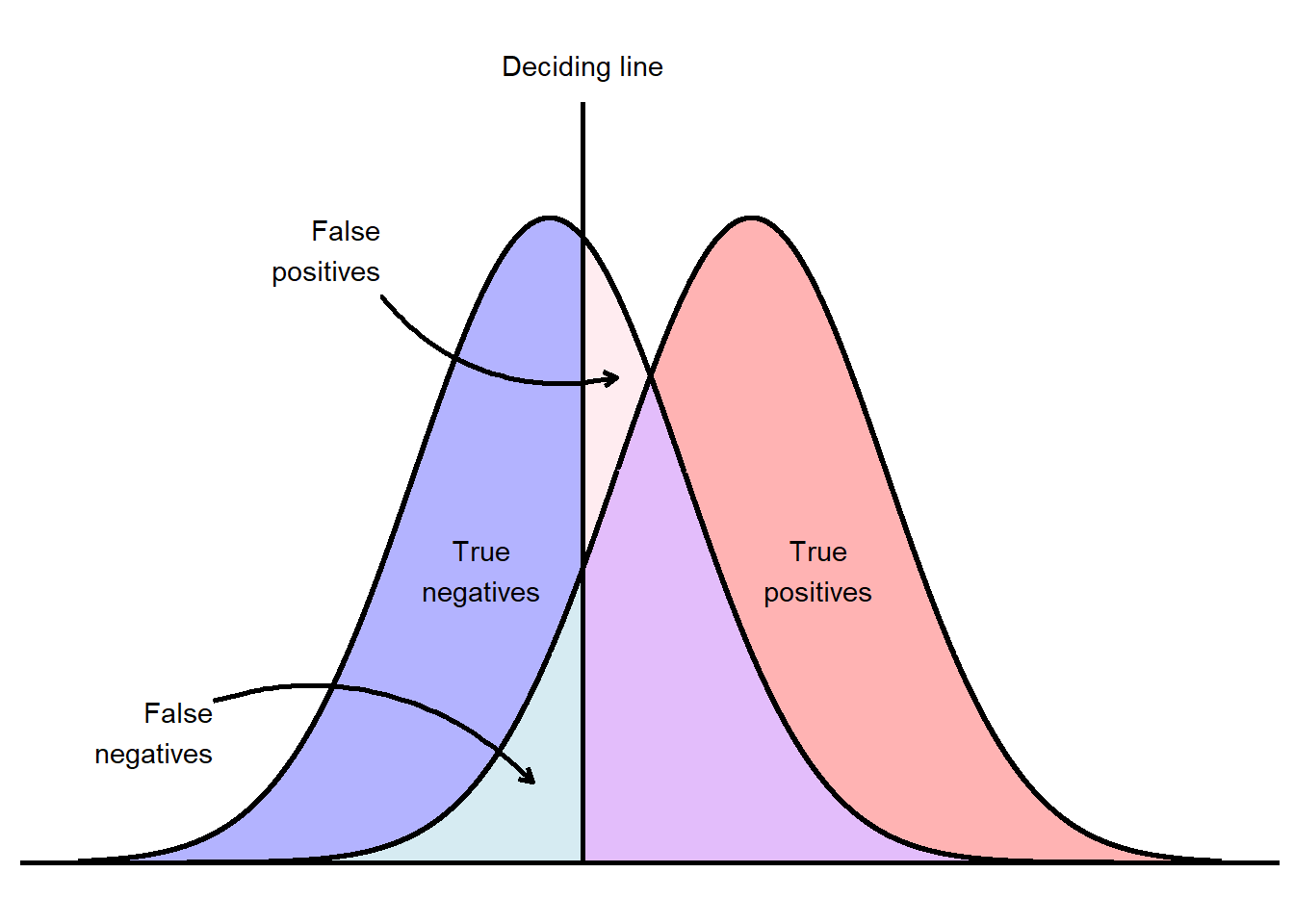

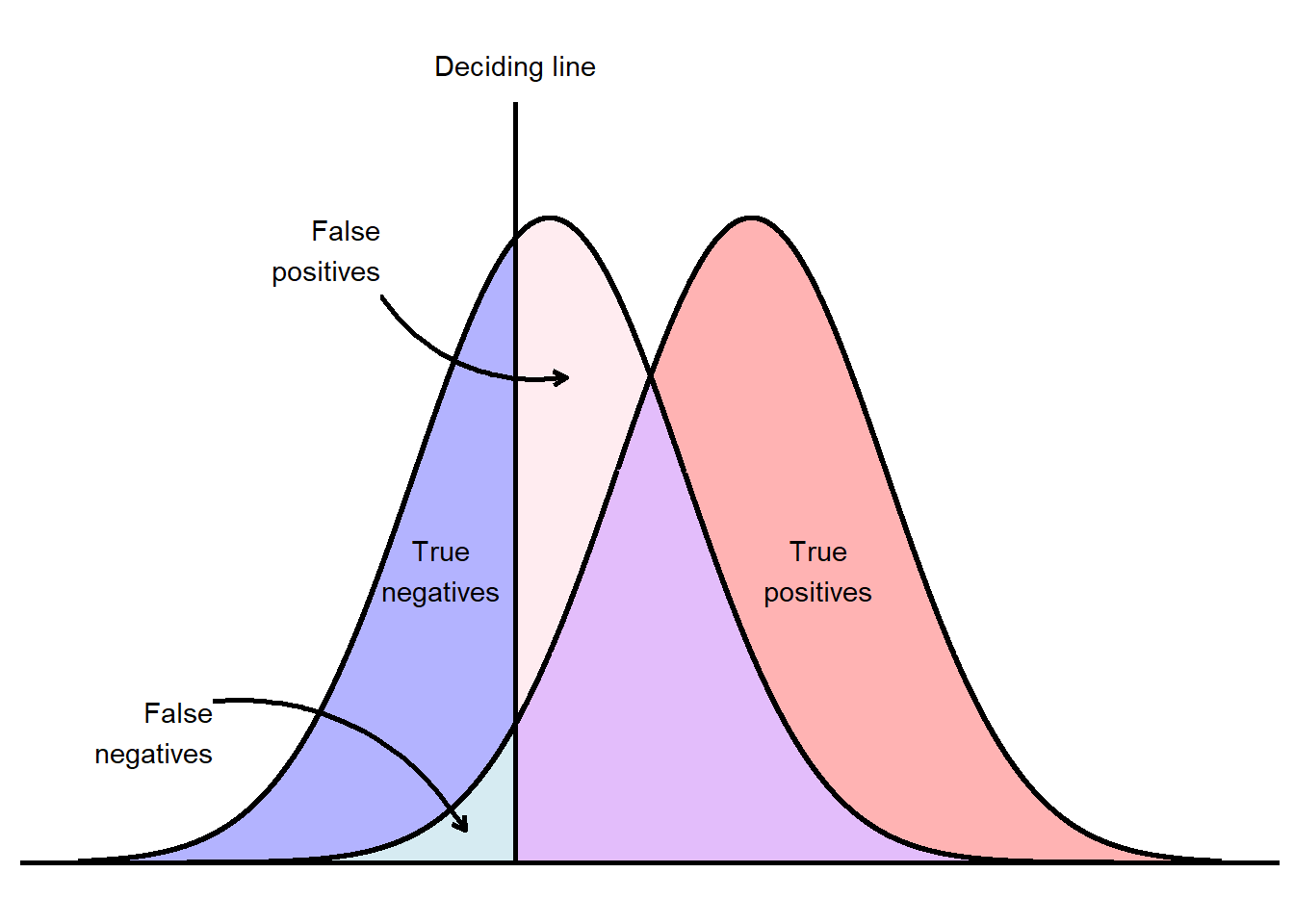

There is no way to avoid this in every case. As a society, we have to weigh the impacts of Type I errors (false positives) against Type II errors (false negatives). Where do we draw the line?

Moving forward, perhaps we should assume that the negative impacts of incorrectly predicting a global pandemic are preferable to the negative impacts of incorrectly predicting that we will avoid a global pandemic. In effect, we would need to give more credence to the growthers way of thinking, and less credence to the base-raters way of thinking - essentially saying that pandemics are more likely to happen than previously thought.

This would move our “deciding line” to the left, resulting in a higher rate of false positives but lower rate of false negatives:

In an increasingly globalized world with interconnected supply chains, interdependencies, and movements of people, I believe this would be prudent. As a culture, we would also need to de-stigmatize those who make dire warnings but turn out to be incorrect. In fact, those who choose to warn early may be wrong many times, but the benefits of listening to them the one time they are right makes them worth listening to.