BradenLive

Things I write live here

Negotiation Analysis: Fall 2019 Weekend Plans

This fall, I wanted to be more intentional with how I spent my time and how my family spent time together on weekends. Knowing the burden of trying to make plans at the last minute while juggling a heavy Kellogg course load, I decided to attempt to plan out every weekend for the next three months, through the end of the fall quarter. When I brought this idea up to my wife, Bethany, she agreed.

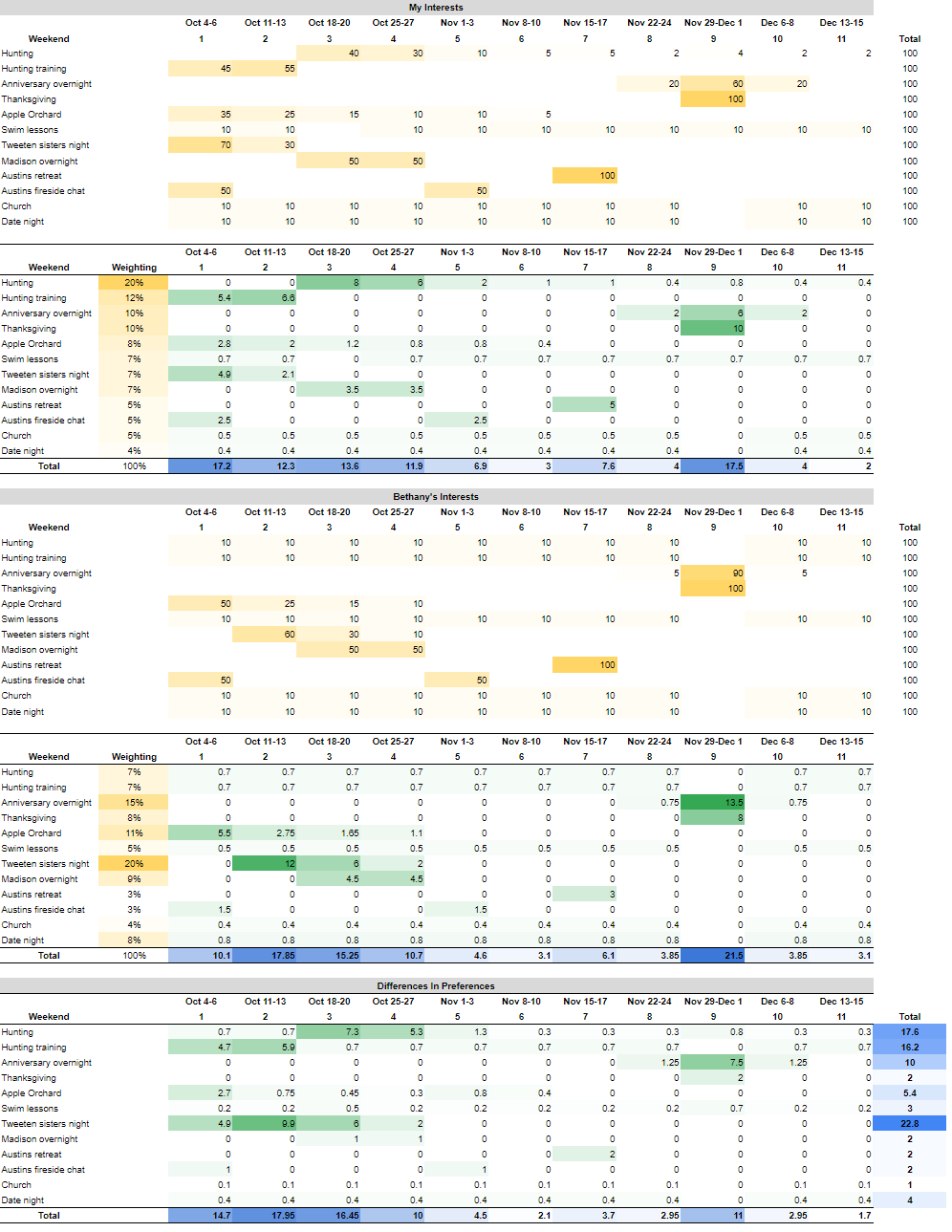

After I prepared extensively, we conducted our negotiation on September 29th. I had identified about a half-dozen issues that were important to me, and an additional half-dozen that I expected would be important to Bethany, shown in Exhibit 1. We conducted the negotiation at our kitchen table. We approached the discussion starting off with our big priorities (we both were very open about what we wanted). Because there were 11 weekends in the fall (October 4th to December 13th), we started our negotiations concentrating on the first few weekends and then moved linearly down the calendar.

Ultimately, we came away with an outcome that we were both happy with, and which did not result in either of us walking away from the table or feeling like we left value on the table. We were able to achieve what we believed to be a pareto-efficient outcome. Along the way, we discovered new information about each other’s priorities that allowed us both to get more value than we had initially expected. Finally, our honest and open approach (necessary in any long-term relationship) facilitated information-seeking and concession-giving. Although this tactic would not be appropriate in every setting, it was the best one for us here. In sum, there were three major factors that led to the negotiated outcome:

- my planning;

- our long-term mindsets; and

- avoiding a dispute.

Effects of Planning on the Outcome

Knowing that I would be writing a graded paper on this negotiation, I naturally prepared quite a bit. The plans for my next 11 weekends were also very important to me, and I wanted to make sure that I wouldn’t leave value on the table, settle for too little, or walk away from the table. I planned in order to avoid these three pitfalls. As shown in Exhibit 1, I began by identifying the discrete issues in play.

| Issues | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| Hunting | Pheasant hunting in Wisconsin with my dog |

| Hunting training | Training my dog for pheasant hunting |

| Thanksgiving | Spending the holiday with family in Milwaukee or Detroit |

| Swim lessons | Taking our daughter to her Saturday morning lessons |

| Austins retreat | Me going away for a night for an Austin Scholars retreat |

| Austins fireside chat | Me attending Austin Scholars fireside chats |

| Church | Attending church weekly on Sunday mornings |

| Anniversary overnight | Going away for one night on our anniversary |

| Apple orchard | Taking our daughter to the apple orchard |

| Tweeten sisters night | Bethany spending a night away with her two sisters |

| Madison overnight | Going away for 1-2 nights in Madison |

| Date nights | Friday or Saturday nights in Evanston or Chicago |

Since none of these issues were quantifiable in terms of a dollar amount or another comparable metric, I found it helpful to create a scoring system, shown in Exhibit 3:

This scoring system helped me determine the priority of issues to me, Bethany’s likely priorities, and a way to offer MESOs. Ultimately, prior planning resulted in a satisfactory outcome for both parties- in previous similar negotiations with no planning, not all issues were addressed and both parties felt unhappy.

To create the scoring system, I distributed 100 points on each issue across the 11 weekends (yellow shaded cells), then weighted each issue according to its importance to me (green shaded cells). This led me to several conclusions: hunting and hunting training were the most important to me, and the first four weekends would be the most valuable to me for these issues (blue shaded cells).

The scoring system also helped me to quantify Bethany’s most likely priorities, and forced me to put myself on the “other side of the table” and think from her point of view. It helped me to realize that I had to temper my expectations of what I could hope to gain from the negotiation, since not all our interests were convergent. It enabled me to construct realistic target price and reservation price, as well as Bethany’s potential target and reservation prices I could expect to be negotiating against.

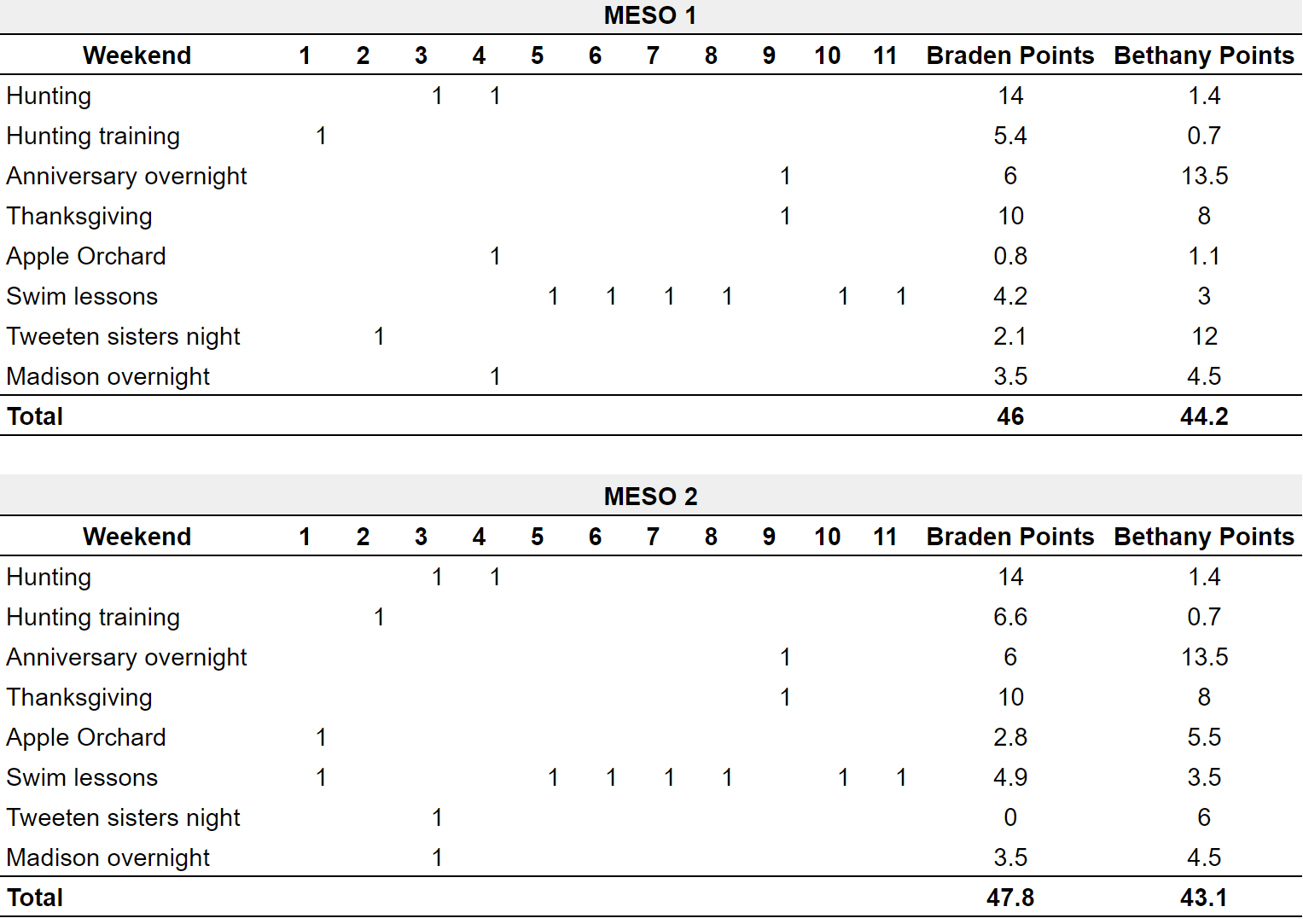

Using the scoring system, I created multiple equivalent simultaneous offer (MESO) packages that would help me to both confirm or deny my expectations of Bethany’s priorities as well as identify ways that we could move towards pareto-efficiency (if the MESOs led to me discovering an issue that Bethany was indifferent about). Exhibit 2 shows the MESOs I offered towards the beginning of the negotiation:

Obviously, I did not offer these in such an explicit manner (although I made sure to offer them as packages, rather than discuss each issue separately). I described the offers to her directly, but I didn’t want to appear too prepared and risk Bethany feeling that she hadn’t adequately prepared. I omitted what I thought would be the least important issues to both of us, in order to simplify the negotiations at the beginning. These secondary issues would be discussed later, during the post-settlement settlement.

Effects of Long-Term Mindsets on the Outcome

Having nearly as large an effect as planning on the outcome of the negotiation, the fact that both Bethany and I had long-term mindsets ensured that we would cooperate with each other. At several points, consideration of future and past negotiations led each of us changing our tactics, positions, or priorities.

As is true in any negotiation, the tension between creating value and claiming it was ever present. At the beginning, I was hesitant to take insincere or aggressive positions with Bethany, that could result in her concluding that I was negotiating without her interests in mind and result in a scorched-earth strategy on her part. For example, the MESOs I suggested did not claim all four of my top priorities- hunting both weekends 3-4 and hunting training both weekends 1-2, even though this would have been in line with my target price. If I had done so, it is likely that Bethany would have responded by not budging on her positions on the Tweeten sisters night/Apple orchard issues on weekends 1-2. If she had taken this position, it would have precluded my ability to do any hunting training at all. Clearly, by trying to create value for both parties, I was able to engender trust and a reciprocal strategy from her. We managed to end up in the “cooperate/cooperate” cell of the Negotiator’s Dilemma grid, knowing there would be many further iterations.

While my top priorities (hunting training and hunting) occurred only in the fall, I knew when we went to plan our winter or spring weekends that my conduct during this negotiation would be remembered. I was therefore careful to not be too aggressive- but I also made clear that I would have more flexibility later on and that Bethany could expect generous concessions when her winter or spring priorities were at stake. Because of our mutual trust, we were able to negotiate in good faith with this understanding. Normally, me asking another party to make concessions without reciprocity would be a poor strategy, but my wife trusted she would be rewarded in the future.

Effects of Interests-Based Negotiating

As mentioned previously, the planning effort I made prior to the negotiation helped me to see Bethany’s point of view on most of the issues, and allowed me to avoid falling into the trap of naïve realism. Devolving into a dispute, perhaps by suggesting that I was entitled to having Bethany choosing between one of the two MESOs I offered, would have likely led Bethany to reject my offers out of hand and led to discussions focused on rights or power of each of the parties, rather than our interests.

Shades of rights-based negotiating did appear, however. For example, I did mention that throughout the rest of the year, I had given Bethany many concessions in terms of her priorities of what to do on our weekends in the winter, spring, and summer- including a trip to Austin, Texas that she had suggested. Therefore, I insinuated that she owed me some concessions here. This did not go over well. Clearly, the thought behind my effort was true, but I did not package it as an opportunity for her to meet my interests as I had. Instead, I acted entitled to a concession from her. Luckily, I was able to backtrack on this and rephrase in a better way. Luckily, our negotiation never devolved into one based on the power dynamic between us- likely because we had mutual trust and respect for each other, and also since we consider ourselves equal in the relationship.

Learnings

Both Bethany and I learned several things from this negotiation. First, the effects of planning cannot be overstated. We both noticed that due to my extensive planning, we were able to achieve a much more mutually valuable outcome than in previous similar negotiations. Planning can benefit both parties. Second, we learned that for these types of negotiations, we didn’t need to be as self-interested as we would have expected. Since our interests actually aligned more than we thought due to each of us wanting the other party to also be satisfied, we were able to get more out of the negotiation. Finally, I learned that quantifying my preferences on each issue, and prioritizing them, enabled me to think more clearly and rationally about various packages that were on the table. I was able to detach emotionally and think more objectively. This also helped me to avoid thinking in terms of my rights or power over Bethany, which ultimately helped me avoid confrontation.

We both decided that in the future, we should be intentional about our plans. It enabled us to achieve our goals more fully and created a much less stressful process for making decisions.