BradenLive

Things I write live here

The Future of Artificial Intelligence in the Department of Defense

Disclosure: My next assignment after graduating from Kellogg will be working as a product manager at the Department of Defense’s new epicenter for artificial intelligence, the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center (JAIC). I wrote this post as an assignment for a class at Kellogg, “Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work.” All information used here is publicly available.

⚠ As mentioned on my About page, The views expressed here are my own and do not reflect those of the Department of Defense, the Navy, or any other government entity.

In 2015, The Defense Business Board published a report, “Transforming DoD’s Core Business Processes for Revolutionary Change”. The report detailed inefficiencies in the Department of Defense’s (DoD) business processes to the tune of $125 billion. One of the report’s key takeaways was that “significant legacy technology obsolescence must be addressed to achieve agility and innovation going forward” in order to reduce these inefficiencies.

At the same time, the last two presidents have directed the DoD to shift focus from counter-insurgency operations to near-peer competition. Part of this shift has entailed understanding the gains that potential adversaries like Russia and China have made in cutting the United States’ technological advantage, making investments to ensure the U.S. maintains a competitive edge.

Serving both these ends, in 2018 the DoD released its Artificial Intelligence Strategy. Two of the goals of the AI Strategy are to 1) “create an efficient and streamlined organization” and 2) “protect our country and safeguard our citizens.” In short, the DoD intends to harness the power of artificial intelligence (AI) to both transform its business processes as well as the application of force on the battlefield. This strategy has major implications for the future of work within DoD as well as the future of warfare. Many employees will become more effective at their jobs due to efficiencies realized through AI. On the other hand, the vast bureaucracy that is the DoD ensures that some jobs will simply become redundant and be completely eliminated. The nature of warfare has the potential to vastly change as well. AI will speed up human decision-making, make new applications of weapon systems possible, and revolutionize military strategy and tactics.

Before DoD can take advantage of AI, however, it must implement two frameworks upon which AI applications can be built:

- Ethical standards for the use of AI

- Information Technology (IT) infrastructure built to handle AI

DoD has made progress on both. We’ll examine these and then look at some of the AI solutions that will potentially change the way DoD runs, both in business and in warfare, over the next few years.

Ethics Principles

In 2019, the Defense Innovation Board (DIB) released, and the DoD subsequently adopted, the following principles for the ethical use of AI. These principles clearly were informed by the consensus forming around Principled AI. The Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard conducted an analysis of the various sets of AI principles released over the last 5+ years and showed the prevalence of eight key themes for principled AI:

| DoD | Berkman Klein Center |

|---|---|

| Responsible | Privacy |

| Equitable | Accountability |

| Traceable | Safety and Security |

| Reliable | Transparency and Explainability |

| Governable | Fariness and Non-Discrimination |

| Human Control of Technology | |

| Professional Responbility | |

| Promotion of Human Values |

It should be noted that the DoD’s AI principles are “aligned with DoD’s mission to deter war and protect our nation. Further, these principles are consistent with existing policy frameworks, the Law of War, domestic law, such as Title 10 of the U.S. Code, and enduring ethical norms that reflect democratic values.”1 It is fair to say that in fact, due to its position as an organ of government, DoD must implement AI to a higher ethical standard than companies in the private sector, which are less restricted by policy. While this higher standard has the purpose of ensuring all DoD AI applications maintain an ethical standing, it also implies that AI in the Department will evolve at a slower pace than in the private sector, due to increased friction. Moving forward, it will be imperative for DoD to maintain connections with the private sector innovators in AI in order to keep pace.

Infrastructure

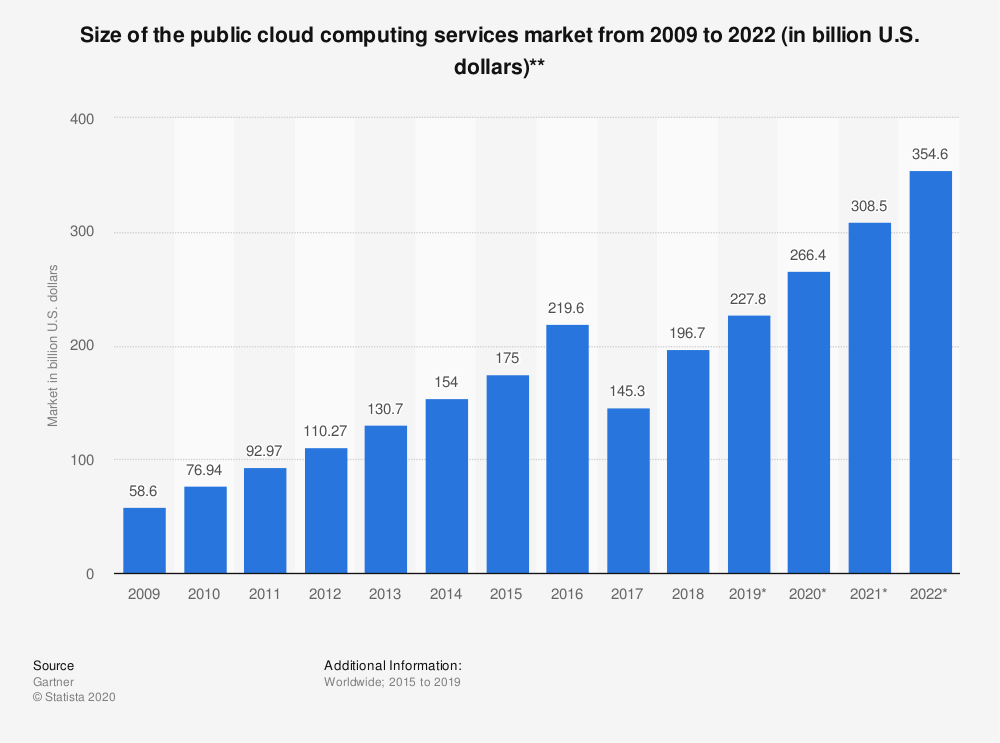

The environment for development of AI technology has only developed in the last decade with the proliferation of cloud services, providing both the engine (distributed computing) and fuel (data) for AI algorithms:

The DoD’s cloud strategy (as of 2018) stated:

The Department of Defense (DoD) has multiple disjointed and stove-piped information systems distributed across modern and legacy infrastructure around the globe leading to a litany of problems that impact warfighters’, decision makers’, and DoD staff’s ability to organize, analyze, secure, scale, and ultimately, capitalize on critical information to make timely, data-driven decisions.

DoD has not kept up with the private sector in building up infrastructure that seeds AI capabilities. This is set to change over the next few years, as Project JEDI, once it clears litigation from Amazon and other cloud providers, is designed to bring all DoD IT systems onto a single cloud-based structure. JEDI will put both data storage and distributed compute resources at the fingertips of users across the DoD.

The JAIC’s Joint Common Foundation (JCF) will build on this cloud infrastructure to “provide the development, test, and runtime environment and the collaboration, tools, reusable assets, and data that military services need to build, refine, test, and field AI applications.”2 The JCF will reduce technical barriers to AI adoption, create standardized tools for AI development, and encourage efficiencies by finding repeatable and scalable processes for AI development within DoD.

Project JEDI, and the JCF layered on top of it3, set the conditions for DoD to rapidly develop AI solutions across the Department. Up until now, AI procurement has been through the traditional contracting process to outside firms. Soon, AI will be produced by users for users, bringing DoD up to speed rapidly.

Future of Work in DoD Vignette: Human Resources Management

Currently, all military personnel are assigned their roles via a centralized office - in the Navy, for example, this is known as the Bureau of Naval Personnel (BUPERS). Within BUPERS, individual servicemembers are controlled by “detailers” within their professional field. These detailers manage the flow of the servicemembers for whom they are responsible to and from various job assignments around the world. Major variables influencing to which jobs servicemembers are assigned include their seniority and rank, required career milestones, and especially timing. In the past, this has been managed by detailers using hand-crafted Excel spreadsheets and whiteboards (colloquially known as “Ouija boards” for their inscrutability). The detailers assess assignments in batches, finding open positions and then candidates who fit based on timing and the other previously mentioned variables. In general, the preferences of the servicemember fall subordinate to the “needs of the service” – practically speaking, this means that the servicemember has very little say in where they will be assigned. This process also results in inefficiencies, because detailers cannot plan more than one or two steps ahead, and ultimately have to make suboptimal assignments. Many servicemembers leave military service because they find this process frustrating and opaque.

The Navy has recognized this problem, and over the past two years has built a two-sided marketplace for detailing. Another solution being piloted within the small Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) officer field is known as the Jetstream Detailing Marketplace. Jetstream acts as a two-sided platform, allowing EOD officers to see all available postings with descriptions and requirements. They can enter their preferences and communicate with the detailer to ask questions. The detailer has an enhanced view of all available postings and can easily identify candidates for upcoming openings. Over time, this assignment data will be captured and used to build predictive models that will allow the EOD officer community to forecast personnel shortfalls, factors influencing the most popular job postings, and more. Currently, that data resides in the head of the detailer, and when the detailer himself is reassigned, most of the institutional knowledge is lost or must be re-learned by the next detailer.

Although this is not a crowdsourced workforce per se, once solutions like Jetstream are rolled out across the DoD, every single servicemember will experience greater agency over their career, improving morale in the short term and retention in the long term. The military will increase productivity due to better matching of talent and passion with available positions. In the very long term, the idea of two-sided matching could lead to a more distributed and horizontal organization chart within the military - still regimented as is required by the military profession and culture, but with some common characteristics of an adhocracy.

Future of Warfare Vignette: Computer Vision

In military command and intelligence centers around the world, analysts pore over live video for hours at a time – working to identify objects on the screen or keeping an eye out for particular events to occur. Project Maven, a contract between the DoD and Google which ended in 2018, was meant to reduce the amount of hours spent on this mind-numbing and repetitive task. Since Project Maven ended4, the JAIC has built upon the computer vision successes for several other uses.

Together with a company called CrowdAI, the JAIC built a product called FireNet, which uses computer vision to provide real-time segmentation of a forest fire perimeter from aerial full-motion infrared video. Previously, this task was completed manually, sapping hours of work and delaying first responders in reacting to the fire: “an analyst must manually point-and-click for hours-on-end to create a fire perimeter polygon, often while working around-the-clock shifts”5. While this solution seems outside what may seem like typical military responsibilities, it actually is very relevant – the California Air National Guard is responsible for using aircraft to observe and respond to fires in that state. A similar AI application being funded by the JAIC and the Defense Innovation Unit will be used during military humanitarian assistance/disaster response missions to assess damage to structures after hurricanes, earthquakes, or fires.

In both of these examples, the AI is performing repetitive and data-heavy tasks, relieving humans of the time and effort necessary to do so themselves. This is the perfect type of application for AI – freeing up humans to perform higher-level cognitive tasks; for instance, building missions based on intelligence collected by Project Maven, alerting first responders to high-priority fires, etc. Humans will always double-check that the has correctly labeled the true positives, so the systems are optimized to minimize false negatives. Therefore humans remain in the loop.

Computer vision also has the potential to be used directly on the battlefield rather than through overhead imagery. A Israeli company called Smartshooter has developed computerized rifle sights which are able to lock onto enemies in the sight’s view, and then help the operator make an accurate shot6. Solutions like this would be used on the battlefield every day, making soldiers more accurate and helping to avoid hitting anything unintended. Additionally, U.S. forces overseas face a growing threat from drones, which enemy combatants have modified to drop grenades. These drones are extremely difficult to hit with rifles, but the computerized scope is able to lock onto these drones and make accurate shots. This reduces the threat to operators in combat. In the long term, tactics and strategy will evolve to include the value of computerized sights like the one from Smartshooter – for instance, placing a few computerized sights in each squad reduces the need for the squad to avoid areas where enemy drones are active, giving more freedom to troops on the ground.

DoD Leading Into the Future

The two vignettes above highlight instances of a greater trend: AI is primed and ready to be utilized in applications across DoD. This revolution is already happening, and will transform the conduct of the Department in both business and warfare. Laying the groundwork for these revolutions, the JAIC and others have built the required ethics and IT infrastructures, which mirror the digital transformations happening in the private sector. Although the DoD AI Strategy holds a goal to “become a pioneer in scaling AI across a global enterprise,”7 it remains to be seen if DoD will end up being a true leader in this area or continue to follow behind the leadership of other global enterprises (either states like Russia or China, or corporations like Microsoft or Google). Either way, the future of work in DoD stands to substantially change in both the near and long terms due to the adoption of AI.

https://media.defense.gov/2019/Oct/31/2002204458/-1/-1/0/DIB_AI_PRINCIPLES_PRIMARY_DOCUMENT.PDF↩

https://www.ai.mil/blog_03_25_20-developing_the_jcf_dhodges.html↩

In the last few weeks, it has become clear that the JCF will instead be layered on top of a different cloud from the Air Force called CloudONE. The benefits will be similar, and ultimately the JCF will be transitioned to JEDI after the litigation is resolved.↩

Google employees successfully petitioned the company to not renew the Project Maven contract with DoD.↩

https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/gyz35j/spotting-wildfires-is-slow-manual-work-ai-could-change-that↩

I highly recommend watching this video to fully understand how it works.↩

https://media.defense.gov/2019/Feb/12/2002088963/-1/-1/1/SUMMARY-OF-DOD-AI-STRATEGY.PDF↩